Experts: Antiquated flu vaccine system needs Monkey Pus update (MB)

http://www.boston.com/yourlife/health/diseases/articles/2003/12/21/experts_a

ntiquated_flu_vaccine_system_needs_updating/

By Paul Elias, Associated Press, 12/21/2003

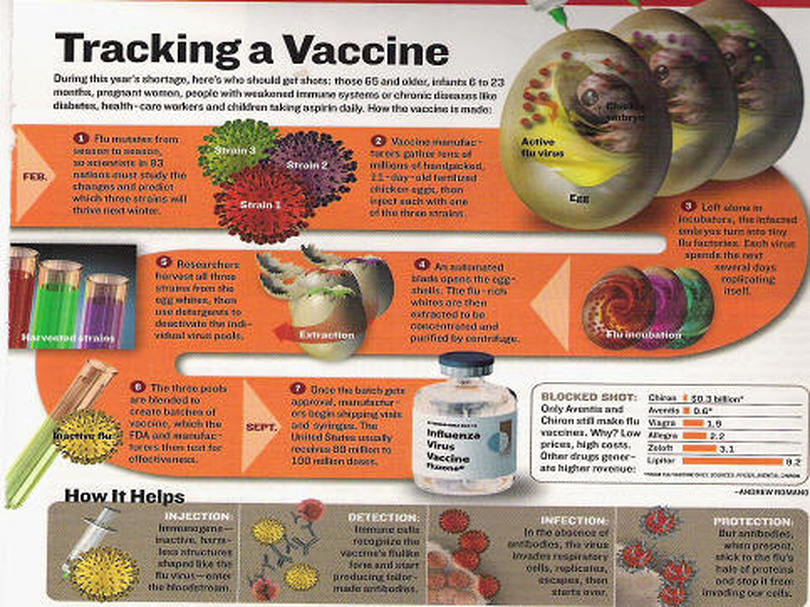

SAN FRANCISCO -- The nation's anxiety over the dwindling supply of flu shots has exposed an antiquated manufacturing system that depends on 90 million fertilized chicken eggs and a 9-month process to produce each year's batch of influenza vaccines. It needn't be that way.

Drug companies and academic researchers say they could reduce the lead time and prepare more effective vaccines by incubating the virus in monkey cells rather than eggs -- and by using genetic engineering to remove much of the guesswork of preventing a disease that kills an average of 36,000 Americans a year.

Government indifference, business resistance and public apathy have slowed the adoption of such techniques, vaccine researchers say. But that may change soon now that federal health officials have responded to the vaccine shortage with calls for overhauling the system. "In order to scale it up, or to speed it up, we would have to, really, change the overall approach to vaccination," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Julie Gerberding said recently, endorsing the monkey cell process as an important alternative.

Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson added last week that he hopes some of the new federal funding for flu research will be used to encourage companies to develop new, egg-free ways to manufacture the vaccines. The federal interest heartens researchers like Dr. Richard Webby, who has labored in relative obscurity for years trying to speed up production of better vaccines.

Webby's work has gotten a lot more attention since it became known that this year's flu vaccine doesn't contain the prevalent strain of the virus going around. The world's two largest manufacturers subsequently announced they had run out of supplies for the first time, even as flu deaths mounted. One 7-year-old Bakersfield boy succumbed while sleeping under his Christmas tree.

"It's tragic that it has happened this way." Webby said. "But if it helps make the process more efficient, that will be a benefit." Each February, World Health Organization doctors meet with an international team of virologists to identify the flu strains they think will hit the following winter. They then brew these flu strains in chicken eggs to create a safe "seed vaccine." It can take weeks or months for the eggs to yield the seed vaccine, and until the vaccine makers receive the seed and related biological material from the World Health Organization, they can't begin the manufacturing

process in earnest.

Webby and colleagues at St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., hope to speed development of each year's vaccine through "reverse genetics," which aims to build from scratch perfect flu strains that reproduce reliably and quickly. "Although the viruses still have to be grown up in eggs to make vaccines, the initial process of making seed vaccine is much quicker using reverse genetics," Webby said. An even bigger time-saver will come from growing the vaccine in vero cells -- taken from the kidneys of African green monkeys -- instead of the chicken eggs, Webby and many others say.

Using vero cells isn't new -- they've have already been used to make a polio vaccine approved in the United States, and a smallpox vaccine using vero cells is in the works. And while people allergic to eggs are advised not to take flu shots, allergic reactions aren't expected to result from the monkey process, since the cells have been purified to eliminate all genetic traces of monkeys from the resulting vaccines. At least two companies, Chiron Corp. and Baxter International, plan large-scale human experiments next year with cell-made vaccines. Each hopes for U.S. regulatory approval in 2007 or soon after.

"There is a certain limitation on how many eggs you can get in a timely manner," said Wayne Morges, a Baxter vice president. "You can't go to the chicken and say 'lay faster.' We can make course corrections easier with cells." Baxter of Deerfield, Ill. is putting the finishing touches on a new factory in the Czech Republic to brew its new vaccine recipe. Baxter hopes to have European approval in time for the 2005 flu season.

Emeryville-based Chiron and the French-owned Aventis Pasteur make the only egg-based flu vaccines approved for use in the United States, and since cell-based vaccines remain years away from the market, Chiron isn't ready to abandon the egg-based process. "It does have the potential to reduce that time, Chiron spokesman Rod Budge said. "But it's not going to produce vaccines overnight." Egg-incubated vaccines will remain the dominant product for at least the next few years not only because of regulatory issues but also because building new factories will take time and money. Baxter also conceded that its initial vaccine shots will cost more than the ones currently available.

Aventis Pasteur remains resistant to changing its egg-based process. Aventis spokesman Len Lavenda argues that the number of new factories and fermenters needed to satisfy demand for the flu shots are not available and will be expensive to build. Also, he said, this flu season is the first in which demand outstripped supply -- it may turn out to be an anomaly. "This is unprecedented because we can't remember a time when we ran out of flu vaccine," Lavenda said. "Public health needs will continue to be best met by egg-based vaccines."

February 23, 2004

http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?chanID=sa004&articleID=0005CA0F-B46F-101E-B

40D83414B7F0000

VACCINES

Egg Beaters

Flu vaccine makers look beyond the chicken egg

By Karen Hopkin

Image: BETTMANN/CORBIS

OVER EASY? Researchers hope to replace the decades-old way of making flu vaccines, which involves injecting viruses into fertilized eggs pierced with a drill. If you want to make an omelet, you have to break some eggs. And if you want to supply the U.S. with flu vaccine, you have to break about 100 million.

That may change someday, as leading vaccine manufacturers explore the possibility of trading their chicken eggs for stainless-steel culture vats and growing their flu virus in cell lines derived from humans, monkeys or dogs. The technology could allow companies to produce their vaccines in a more timely and less laborious manner and to respond more quickly in an emergency.

Today's flu vaccines are prepared in fertilized chicken eggs, a method developed more than 50 years ago. The eggshell is cracked, and the influenza virus is injected into the fluid surrounding the embryo. The egg is resealed, the embryo becomes infected, and the resulting virus is then harvested, purified and used to produce the vaccine. Even with robotic assistance, "working with eggs is tedious," says Samuel L. Katz of the Duke University School of Medicine, a member of the vaccine advisory committee for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Opening a culture flask is a heck of a lot simpler."

Better yet, using cells could shave weeks off the production process, notes Dinko Valerio, president and CEO of Crucell, a Dutch biotechnology company developing one of the human cell lines. Now when a new strain of flu is discovered, researchers often need to tinker with the virus to get it to reproduce in chicken eggs. Makers using cultured cells could save time by skipping that step, perhaps even starting directly from the circulating virus isolated from humans. As an added bonus, the virus harvested from cells rather than eggs might even look more like the virus encountered by humans, making it better fodder for a vaccine, adds Michel DeWilde, executive vice president of R&D at Aventis, the world's largest producer of flu vaccines and a partner with Crucell in developing flu shots made from human cells.

Whether vaccines churned out by barrels of cells will be any better than those produced in eggs "remains to be seen," says the FDA's Roland A. Levandowski. And for a person getting jabbed in the arm during a regular flu season, observes Richard Webby, a virologist at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., "it's not going to matter where the vaccine came from."

http://www.620ktar.com/news/article.aspx?id=482888

10/23/2004 3:51:00 PM

Vaccine Production Relies on Quaint System

By MARILYNN MARCHIONE AP Medical Writer

The quaint system of producing flu vaccine based on seasonal egg-laying has harsh implications for what would happen if new batches had to be made in a hurry to fight a super-strain pandemic. At best, it would take half a year.

And since chicken flocks for next year's vaccine are already established and plants already run at full capacity, it's unclear how much Aventis Pasteur or any single company can goose up production to cover a shortfall like this year's loss of Chiron Corp.'s vaccine. As Chiron executive Dr. Kevin Bryett said in an interview two weeks before its British factory was shut down: "If the market was to change

dramatically, it is almost impossible to turn up production. The primary issue is access to the eggs. Large numbers of birds cannot be obtained immediately. It's not something you can just go down to the shop and buy, eggs off the shelf." A visit to Aventis, America's only flu shot maker, reveals how much fragile Americans depend on an eggshell-fragile system to protect them from a killer disease. The Associated Press was allowed inside last week for a rare, firsthand look.

As the nation struggles with a historic shortage of flu vaccine, the last batches of this year's supply are being bottled at a slickly run, modern factory in the Pocono Mountains. A little to the west, in Amish country, next year's doses are already in the works. At the moment, they have two legs and soft, downy feathers. By January, they'll be laying millions of eggs for flu shots. There is far more horse-and-buggy to vaccine production than just the Amish wagons that creak past Pennsylvania chicken farms. Vaccines are biological products, not chemicals that can be cranked out in times of need.

The viruses they're made from need cells in which to grow. Yellow fever and flu are the only vaccines that use eggs for this _ not the kind that come from the store but those produced under strict pharmaceutical conditions.

Flu also is the only vaccine made fresh every year. In late February or early March, the World Health Organization picks its three strains based on the virus going around. If it acts too soon, newly emerging strains can be missed, as Fujian was last year. If it waits too long, vaccine makers must race against the biological clocks of hens, which only lay eggs for nine months until they're too old, then rush through a several-months-long process to make enough vaccine before the flu season starts. "We're constrained on the front end and the back end. No other vaccine has that kind of time pressure," said Aventis spokesman Len Lavenda. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the government's top vaccine scientist, acknowledged the difficulty.

"The ability to have surge capacity when something goes wrong, to turn on a dime and try and correct it, is difficult," he said in an interview Thursday. Aventis starts making vaccine more than a year in advance, around August on nearly 50 farms throughout Pennsylvania. "They're fairly small operations," many with only 10,000 birds, said Sam Lee, a 40-year-old chemical engineer who is the company's operations team leader. White leghorn hens are used. The exact type is a company secret. The breeder holding the patent supplies the eggs, which take 21 days to hatch and become

chicks.

They're moved in late September into buildings where they can move freely as opposed to cages and coops, and spend three months maturing into hens. Egg-laying starts in late December, typically one a day. How many eggs it takes to make a flu shot is another Aventis secret, but Chiron's Bryett said: "If you're very lucky, you'll get three doses per egg." That's for a single flu strain; three strains go into each dose of vaccine. The fertilized eggs are collected by two large egg producers, who incubate them for seven to 12 days and then bring them to Aventis. Eggs delivered in January would hatch into chicks if not used for vaccine, so manufacturers often gamble and start making whichever of the three flu strains WHO seems most likely to choose.

"Any production before February is done at the company's risk," Lee said.

A machine punches a tiny hole in each shell and a needle inoculates the chick embryo with a single flu strain. The virus is allowed to multiply for about three days. Then the eggs are broken, and the fluid around the embryo containing the virus is collected and purified. Formaldehyde is added to inactivate the flu virus, and a machine spins the mixture to separate out the part containing virus. Once again, eggs are needed: A sample of the spun solution is put back in the eggs to see if any virus grows _ a test to ensure the germ was inactivated. A few more processing steps turn it into a lot, or batch, of several hundred thousand doses of a single strain.

Next comes sterility testing where vaccine is spread onto lab dishes and checked to see if it contains contaminating bacteria. "We haven't had a contamination in years," Lee said.

It's not known whether this step is where Chiron's vaccine was discovered to be tainted with serratia bacteria or if it happened later. As Aventis tests for sterility, samples also go to the Food and Drug Administration, which doesn't start its testing until late May or early June because it has to brew specific chemicals each year to test specific strains. After that, three viral strains are combined to form the trivalent vaccine. Four weeks of potency and sterility testing follow, then packaging into single-dose syringes and 10-dose vials and quality checks for potency.

The last doses are made by the end of September. Chicken farms are free to sell old birds and must do a mandatory cleanout and disinfection to get ready to start the whole process all over again. As cumbersome as this egg-based vaccine recipe may seem, "it has been over the years a reliable, time-tested and reasonably efficient way to get virus grown," Fauci said. "Changing that requires genuinely a very, very large investment" to make a product sold only once a year and for a pittance compared to expensive cholesterol pills and other drugs that people take every day, said Dr. William Schaffner, a Vanderbilt University flu expert who advises the government on vaccines.

"Vaccines in general and flu in particular are undervalued. Prices are not at the level they should be to attract new investments," Aventis' Lavenda agreed. Aventis has partnered with a company in the Netherlands, Crucell, to research using human and animal cells in place of eggs. These so-called cell cultures could be maintained indefinitely and ramped up on demand whenever vaccine is needed. It's pricey technology, but cost isn't the only obstacle. Some worry that the genetic material of these cells might interact with the flu viruses, creating dangerous hybrids and undercutting the purpose of the vaccine.

"If it changes the virus, obviously, that would not be desirable," Chiron's Bryett said. Such technology is at least a couple years away, said Fauci, whose office is funding many such studies. "There are safety issues, consistency issues," he said. "That's the reason why you do research on it. If it was just sticking the virus in a cell culture and go, we would have done it a long time ago." So we're stuck with eggs for next year and probably several more. The government has plans in the works to encourage chicken farmers to maintain year-round flocks so eggs would be available anytime in case a new single-strain vaccine had to be made to fight a pandemic.

"Right now we don't have the capacity to reliably create all the vaccine we would need in that situation," Dr. Julie Gerberding, director of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a news conference earlier this year. "It is clear that we need to substantially expand our options," including looking at whether the vaccine really needs to be updated every year, Dr. John Treanor, another government vaccine adviser from the University of Rochester, wrote in a recent New England Journal of Medicine article.

Public health officials have worried much about bioterrorism, a threat of unknown proportions. Instead, Treanor writes, the nation has been caught offguard and threatened by a long familiar foe, "a virus that predictably _ in each and every year _ causes major mortality and morbidity."

http://tinyurl.com/etwew

FDA gives MedImmune OK on new way to make FluMist

Md. biotech to use 'reverse genetics'

By Tricia Bishop

Sun reporter

Originally published July 7, 2006

A technique widely used to produce possible pandemic flu vaccines will soon be used to make at least one seasonal version: MedImmune Inc. announced yesterday that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has given it the go-ahead to create its nasally inhaled FluMist using "reverse genetics."

Though the manufacturing process won't affect the FluMist's formulation or the way it is administered, the technique is thought to be a more efficient and reliable means of production - faster and safer than the current standard. The company says it will be the only vaccine on the market using this technique.

MedImmune, based in Gaithersburg, is hoping that others will follow its lead and license the technology.

"The technique allows the rapid generation of seed viruses for vaccine candidates that exactly match the anticipated epidemic strain," said congressional testimony from Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases - or NIAID.

The typical way of making flu vaccines - called "classical reassortment" - dates to the 1960s and requires a lot of time-consuming guesswork by scientists. It involves injecting two flu strains into a fertilized chicken egg, where they mix and multiply into as many as 256 gene combinations. Researchers then sort through all of those combinations to find the one they want to manufacture as that season's vaccine.

In reverse genetics, scientists can specifically construct the combination of flu strains they need. They do this by splicing genes together and manufacturing the seeds of the vaccine in mammal cells - in MedImmune's case, kidney cells from an African green monkey. They also can remove any harmful pieces of the flu virus and modify its reproduction rate.

MedImmune has been working with NIAID to create a library of pandemic flu vaccines from which mass amounts could be made if a pandemic occurred.

The company also has offered to license its reverse genetics technology to others. In December, MedImmune acquired the final exclusive license to the last of four intellectual property portfolios that govern the use of reverse genetics in making human flu vaccines. That means anyone else who wants to get in on it has to get the company's permission first.

"It's a technological improvement over the way things are done today," said Philip Nadeau, a biotechnology analyst with S.G. Cowen & Co. LLC. "It seems to me they should be interested in licensing." He does not own stock in MedImmune, nor does his company have an investment relationship with MedImmune.

Nadeau also said the technology should help MedImmune "improve the reliability of FluMist's production."

FluMist's record has been marked by disappointing sales, overproduction and under-adoption.

A second-generation of the vaccine, called CAIV-T, , is under development, and should be ready by the 2007-2008 flu season. MedImmune is hoping CAIV-T doesn't have the same problems that FluMist has encountered. That version was approved for a limited population, and some had concerns that the live virus it's based on would make them sick.

MedImmune's stock closed up a penny to $26.61 on the Nasdaq yesterday.

Though reverse genetics is considered something of an advance in the flu-vaccine world, it hasn't revolutionized the process. It still relies on chicken eggs to reproduce enough of the vaccine to provide doses for the population, a process that President Bush called "antiquated" last year.

Several groups are trying to develop a cell-based production process that would take the chickens out of the mix. MedImmune has been given a $170 million contract from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to study the possibility of producing the vaccine using cells such as the monkey's, which would make it available to people who have poultry allergies and can't receive the vaccines.

"That's still several years away from being a tangible product, but there's a lot of work going on right now." said George W. Kemble, vice president of research and development at MedImmune Vaccines Inc., a Mountain View, Calif.-based arm of the Gaithersburg biotechnology company.

Last fall, Bush asked Congress for several billion dollars to develop a "crash program" of cell-based manufacturing for pandemic influenza vaccines. The technique has been used since the 1950s to create vaccines for diseases, including polio, measles and mumps.

But flu vaccine manufacturers have avoided it, sticking with the tried and true egg method, in part because changing the system will likely cost billions of dollars.

http://www.boston.com/yourlife/health/diseases/articles/2003/12/21/experts_a

ntiquated_flu_vaccine_system_needs_updating/

By Paul Elias, Associated Press, 12/21/2003

SAN FRANCISCO -- The nation's anxiety over the dwindling supply of flu shots has exposed an antiquated manufacturing system that depends on 90 million fertilized chicken eggs and a 9-month process to produce each year's batch of influenza vaccines. It needn't be that way.

Drug companies and academic researchers say they could reduce the lead time and prepare more effective vaccines by incubating the virus in monkey cells rather than eggs -- and by using genetic engineering to remove much of the guesswork of preventing a disease that kills an average of 36,000 Americans a year.

Government indifference, business resistance and public apathy have slowed the adoption of such techniques, vaccine researchers say. But that may change soon now that federal health officials have responded to the vaccine shortage with calls for overhauling the system. "In order to scale it up, or to speed it up, we would have to, really, change the overall approach to vaccination," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Julie Gerberding said recently, endorsing the monkey cell process as an important alternative.

Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson added last week that he hopes some of the new federal funding for flu research will be used to encourage companies to develop new, egg-free ways to manufacture the vaccines. The federal interest heartens researchers like Dr. Richard Webby, who has labored in relative obscurity for years trying to speed up production of better vaccines.

Webby's work has gotten a lot more attention since it became known that this year's flu vaccine doesn't contain the prevalent strain of the virus going around. The world's two largest manufacturers subsequently announced they had run out of supplies for the first time, even as flu deaths mounted. One 7-year-old Bakersfield boy succumbed while sleeping under his Christmas tree.

"It's tragic that it has happened this way." Webby said. "But if it helps make the process more efficient, that will be a benefit." Each February, World Health Organization doctors meet with an international team of virologists to identify the flu strains they think will hit the following winter. They then brew these flu strains in chicken eggs to create a safe "seed vaccine." It can take weeks or months for the eggs to yield the seed vaccine, and until the vaccine makers receive the seed and related biological material from the World Health Organization, they can't begin the manufacturing

process in earnest.

Webby and colleagues at St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., hope to speed development of each year's vaccine through "reverse genetics," which aims to build from scratch perfect flu strains that reproduce reliably and quickly. "Although the viruses still have to be grown up in eggs to make vaccines, the initial process of making seed vaccine is much quicker using reverse genetics," Webby said. An even bigger time-saver will come from growing the vaccine in vero cells -- taken from the kidneys of African green monkeys -- instead of the chicken eggs, Webby and many others say.

Using vero cells isn't new -- they've have already been used to make a polio vaccine approved in the United States, and a smallpox vaccine using vero cells is in the works. And while people allergic to eggs are advised not to take flu shots, allergic reactions aren't expected to result from the monkey process, since the cells have been purified to eliminate all genetic traces of monkeys from the resulting vaccines. At least two companies, Chiron Corp. and Baxter International, plan large-scale human experiments next year with cell-made vaccines. Each hopes for U.S. regulatory approval in 2007 or soon after.

"There is a certain limitation on how many eggs you can get in a timely manner," said Wayne Morges, a Baxter vice president. "You can't go to the chicken and say 'lay faster.' We can make course corrections easier with cells." Baxter of Deerfield, Ill. is putting the finishing touches on a new factory in the Czech Republic to brew its new vaccine recipe. Baxter hopes to have European approval in time for the 2005 flu season.

Emeryville-based Chiron and the French-owned Aventis Pasteur make the only egg-based flu vaccines approved for use in the United States, and since cell-based vaccines remain years away from the market, Chiron isn't ready to abandon the egg-based process. "It does have the potential to reduce that time, Chiron spokesman Rod Budge said. "But it's not going to produce vaccines overnight." Egg-incubated vaccines will remain the dominant product for at least the next few years not only because of regulatory issues but also because building new factories will take time and money. Baxter also conceded that its initial vaccine shots will cost more than the ones currently available.

Aventis Pasteur remains resistant to changing its egg-based process. Aventis spokesman Len Lavenda argues that the number of new factories and fermenters needed to satisfy demand for the flu shots are not available and will be expensive to build. Also, he said, this flu season is the first in which demand outstripped supply -- it may turn out to be an anomaly. "This is unprecedented because we can't remember a time when we ran out of flu vaccine," Lavenda said. "Public health needs will continue to be best met by egg-based vaccines."

February 23, 2004

http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?chanID=sa004&articleID=0005CA0F-B46F-101E-B

40D83414B7F0000

VACCINES

Egg Beaters

Flu vaccine makers look beyond the chicken egg

By Karen Hopkin

Image: BETTMANN/CORBIS

OVER EASY? Researchers hope to replace the decades-old way of making flu vaccines, which involves injecting viruses into fertilized eggs pierced with a drill. If you want to make an omelet, you have to break some eggs. And if you want to supply the U.S. with flu vaccine, you have to break about 100 million.

That may change someday, as leading vaccine manufacturers explore the possibility of trading their chicken eggs for stainless-steel culture vats and growing their flu virus in cell lines derived from humans, monkeys or dogs. The technology could allow companies to produce their vaccines in a more timely and less laborious manner and to respond more quickly in an emergency.

Today's flu vaccines are prepared in fertilized chicken eggs, a method developed more than 50 years ago. The eggshell is cracked, and the influenza virus is injected into the fluid surrounding the embryo. The egg is resealed, the embryo becomes infected, and the resulting virus is then harvested, purified and used to produce the vaccine. Even with robotic assistance, "working with eggs is tedious," says Samuel L. Katz of the Duke University School of Medicine, a member of the vaccine advisory committee for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Opening a culture flask is a heck of a lot simpler."

Better yet, using cells could shave weeks off the production process, notes Dinko Valerio, president and CEO of Crucell, a Dutch biotechnology company developing one of the human cell lines. Now when a new strain of flu is discovered, researchers often need to tinker with the virus to get it to reproduce in chicken eggs. Makers using cultured cells could save time by skipping that step, perhaps even starting directly from the circulating virus isolated from humans. As an added bonus, the virus harvested from cells rather than eggs might even look more like the virus encountered by humans, making it better fodder for a vaccine, adds Michel DeWilde, executive vice president of R&D at Aventis, the world's largest producer of flu vaccines and a partner with Crucell in developing flu shots made from human cells.

Whether vaccines churned out by barrels of cells will be any better than those produced in eggs "remains to be seen," says the FDA's Roland A. Levandowski. And for a person getting jabbed in the arm during a regular flu season, observes Richard Webby, a virologist at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., "it's not going to matter where the vaccine came from."

http://www.620ktar.com/news/article.aspx?id=482888

10/23/2004 3:51:00 PM

Vaccine Production Relies on Quaint System

By MARILYNN MARCHIONE AP Medical Writer

The quaint system of producing flu vaccine based on seasonal egg-laying has harsh implications for what would happen if new batches had to be made in a hurry to fight a super-strain pandemic. At best, it would take half a year.

And since chicken flocks for next year's vaccine are already established and plants already run at full capacity, it's unclear how much Aventis Pasteur or any single company can goose up production to cover a shortfall like this year's loss of Chiron Corp.'s vaccine. As Chiron executive Dr. Kevin Bryett said in an interview two weeks before its British factory was shut down: "If the market was to change

dramatically, it is almost impossible to turn up production. The primary issue is access to the eggs. Large numbers of birds cannot be obtained immediately. It's not something you can just go down to the shop and buy, eggs off the shelf." A visit to Aventis, America's only flu shot maker, reveals how much fragile Americans depend on an eggshell-fragile system to protect them from a killer disease. The Associated Press was allowed inside last week for a rare, firsthand look.

As the nation struggles with a historic shortage of flu vaccine, the last batches of this year's supply are being bottled at a slickly run, modern factory in the Pocono Mountains. A little to the west, in Amish country, next year's doses are already in the works. At the moment, they have two legs and soft, downy feathers. By January, they'll be laying millions of eggs for flu shots. There is far more horse-and-buggy to vaccine production than just the Amish wagons that creak past Pennsylvania chicken farms. Vaccines are biological products, not chemicals that can be cranked out in times of need.

The viruses they're made from need cells in which to grow. Yellow fever and flu are the only vaccines that use eggs for this _ not the kind that come from the store but those produced under strict pharmaceutical conditions.

Flu also is the only vaccine made fresh every year. In late February or early March, the World Health Organization picks its three strains based on the virus going around. If it acts too soon, newly emerging strains can be missed, as Fujian was last year. If it waits too long, vaccine makers must race against the biological clocks of hens, which only lay eggs for nine months until they're too old, then rush through a several-months-long process to make enough vaccine before the flu season starts. "We're constrained on the front end and the back end. No other vaccine has that kind of time pressure," said Aventis spokesman Len Lavenda. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the government's top vaccine scientist, acknowledged the difficulty.

"The ability to have surge capacity when something goes wrong, to turn on a dime and try and correct it, is difficult," he said in an interview Thursday. Aventis starts making vaccine more than a year in advance, around August on nearly 50 farms throughout Pennsylvania. "They're fairly small operations," many with only 10,000 birds, said Sam Lee, a 40-year-old chemical engineer who is the company's operations team leader. White leghorn hens are used. The exact type is a company secret. The breeder holding the patent supplies the eggs, which take 21 days to hatch and become

chicks.

They're moved in late September into buildings where they can move freely as opposed to cages and coops, and spend three months maturing into hens. Egg-laying starts in late December, typically one a day. How many eggs it takes to make a flu shot is another Aventis secret, but Chiron's Bryett said: "If you're very lucky, you'll get three doses per egg." That's for a single flu strain; three strains go into each dose of vaccine. The fertilized eggs are collected by two large egg producers, who incubate them for seven to 12 days and then bring them to Aventis. Eggs delivered in January would hatch into chicks if not used for vaccine, so manufacturers often gamble and start making whichever of the three flu strains WHO seems most likely to choose.

"Any production before February is done at the company's risk," Lee said.

A machine punches a tiny hole in each shell and a needle inoculates the chick embryo with a single flu strain. The virus is allowed to multiply for about three days. Then the eggs are broken, and the fluid around the embryo containing the virus is collected and purified. Formaldehyde is added to inactivate the flu virus, and a machine spins the mixture to separate out the part containing virus. Once again, eggs are needed: A sample of the spun solution is put back in the eggs to see if any virus grows _ a test to ensure the germ was inactivated. A few more processing steps turn it into a lot, or batch, of several hundred thousand doses of a single strain.

Next comes sterility testing where vaccine is spread onto lab dishes and checked to see if it contains contaminating bacteria. "We haven't had a contamination in years," Lee said.

It's not known whether this step is where Chiron's vaccine was discovered to be tainted with serratia bacteria or if it happened later. As Aventis tests for sterility, samples also go to the Food and Drug Administration, which doesn't start its testing until late May or early June because it has to brew specific chemicals each year to test specific strains. After that, three viral strains are combined to form the trivalent vaccine. Four weeks of potency and sterility testing follow, then packaging into single-dose syringes and 10-dose vials and quality checks for potency.

The last doses are made by the end of September. Chicken farms are free to sell old birds and must do a mandatory cleanout and disinfection to get ready to start the whole process all over again. As cumbersome as this egg-based vaccine recipe may seem, "it has been over the years a reliable, time-tested and reasonably efficient way to get virus grown," Fauci said. "Changing that requires genuinely a very, very large investment" to make a product sold only once a year and for a pittance compared to expensive cholesterol pills and other drugs that people take every day, said Dr. William Schaffner, a Vanderbilt University flu expert who advises the government on vaccines.

"Vaccines in general and flu in particular are undervalued. Prices are not at the level they should be to attract new investments," Aventis' Lavenda agreed. Aventis has partnered with a company in the Netherlands, Crucell, to research using human and animal cells in place of eggs. These so-called cell cultures could be maintained indefinitely and ramped up on demand whenever vaccine is needed. It's pricey technology, but cost isn't the only obstacle. Some worry that the genetic material of these cells might interact with the flu viruses, creating dangerous hybrids and undercutting the purpose of the vaccine.

"If it changes the virus, obviously, that would not be desirable," Chiron's Bryett said. Such technology is at least a couple years away, said Fauci, whose office is funding many such studies. "There are safety issues, consistency issues," he said. "That's the reason why you do research on it. If it was just sticking the virus in a cell culture and go, we would have done it a long time ago." So we're stuck with eggs for next year and probably several more. The government has plans in the works to encourage chicken farmers to maintain year-round flocks so eggs would be available anytime in case a new single-strain vaccine had to be made to fight a pandemic.

"Right now we don't have the capacity to reliably create all the vaccine we would need in that situation," Dr. Julie Gerberding, director of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a news conference earlier this year. "It is clear that we need to substantially expand our options," including looking at whether the vaccine really needs to be updated every year, Dr. John Treanor, another government vaccine adviser from the University of Rochester, wrote in a recent New England Journal of Medicine article.

Public health officials have worried much about bioterrorism, a threat of unknown proportions. Instead, Treanor writes, the nation has been caught offguard and threatened by a long familiar foe, "a virus that predictably _ in each and every year _ causes major mortality and morbidity."

http://tinyurl.com/etwew

FDA gives MedImmune OK on new way to make FluMist

Md. biotech to use 'reverse genetics'

By Tricia Bishop

Sun reporter

Originally published July 7, 2006

A technique widely used to produce possible pandemic flu vaccines will soon be used to make at least one seasonal version: MedImmune Inc. announced yesterday that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has given it the go-ahead to create its nasally inhaled FluMist using "reverse genetics."

Though the manufacturing process won't affect the FluMist's formulation or the way it is administered, the technique is thought to be a more efficient and reliable means of production - faster and safer than the current standard. The company says it will be the only vaccine on the market using this technique.

MedImmune, based in Gaithersburg, is hoping that others will follow its lead and license the technology.

"The technique allows the rapid generation of seed viruses for vaccine candidates that exactly match the anticipated epidemic strain," said congressional testimony from Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases - or NIAID.

The typical way of making flu vaccines - called "classical reassortment" - dates to the 1960s and requires a lot of time-consuming guesswork by scientists. It involves injecting two flu strains into a fertilized chicken egg, where they mix and multiply into as many as 256 gene combinations. Researchers then sort through all of those combinations to find the one they want to manufacture as that season's vaccine.

In reverse genetics, scientists can specifically construct the combination of flu strains they need. They do this by splicing genes together and manufacturing the seeds of the vaccine in mammal cells - in MedImmune's case, kidney cells from an African green monkey. They also can remove any harmful pieces of the flu virus and modify its reproduction rate.

MedImmune has been working with NIAID to create a library of pandemic flu vaccines from which mass amounts could be made if a pandemic occurred.

The company also has offered to license its reverse genetics technology to others. In December, MedImmune acquired the final exclusive license to the last of four intellectual property portfolios that govern the use of reverse genetics in making human flu vaccines. That means anyone else who wants to get in on it has to get the company's permission first.

"It's a technological improvement over the way things are done today," said Philip Nadeau, a biotechnology analyst with S.G. Cowen & Co. LLC. "It seems to me they should be interested in licensing." He does not own stock in MedImmune, nor does his company have an investment relationship with MedImmune.

Nadeau also said the technology should help MedImmune "improve the reliability of FluMist's production."

FluMist's record has been marked by disappointing sales, overproduction and under-adoption.

A second-generation of the vaccine, called CAIV-T, , is under development, and should be ready by the 2007-2008 flu season. MedImmune is hoping CAIV-T doesn't have the same problems that FluMist has encountered. That version was approved for a limited population, and some had concerns that the live virus it's based on would make them sick.

MedImmune's stock closed up a penny to $26.61 on the Nasdaq yesterday.

Though reverse genetics is considered something of an advance in the flu-vaccine world, it hasn't revolutionized the process. It still relies on chicken eggs to reproduce enough of the vaccine to provide doses for the population, a process that President Bush called "antiquated" last year.

Several groups are trying to develop a cell-based production process that would take the chickens out of the mix. MedImmune has been given a $170 million contract from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to study the possibility of producing the vaccine using cells such as the monkey's, which would make it available to people who have poultry allergies and can't receive the vaccines.

"That's still several years away from being a tangible product, but there's a lot of work going on right now." said George W. Kemble, vice president of research and development at MedImmune Vaccines Inc., a Mountain View, Calif.-based arm of the Gaithersburg biotechnology company.

Last fall, Bush asked Congress for several billion dollars to develop a "crash program" of cell-based manufacturing for pandemic influenza vaccines. The technique has been used since the 1950s to create vaccines for diseases, including polio, measles and mumps.

But flu vaccine manufacturers have avoided it, sticking with the tried and true egg method, in part because changing the system will likely cost billions of dollars.