http://www.abcnews.go.com/wire/US/ap20040210_549.html

Colorado Last in Child Immunization Rate

Colorado Ranks Last in Government Survey of Child Vaccination Rates; Poverty, Shortages Cited

The Associated Press

DENVER Feb. 10 — Every few months, Erin Dlouhy sees a child under 2 at Samaritan House who has never had shots for polio, measles or whooping cough. Other children at the homeless shelter lack medical records and have to endure the painful shots again. "I would say at least 50 percent of the time, kids need to be caught up," said Dlouhy, coordinator of children's services at the shelter.

For reasons that include poverty, a lack of government funding and a national shortage of the whooping cough vaccine, Colorado wound up last in the government's most recent survey of child vaccination rates.

"We're at the bottom of the barrel," said Dr. Marsha Anderson, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Children's Hospital in Denver. "Our goal should be to be in the top 10 to be able to provide adequate coverage of our children."Health advocates say children in a state proud of its well-educated and healthy population are at risk because of funding cuts at the state and local level. They also say some parents simply do not have the money to pay for the shots or lose track of what is required.

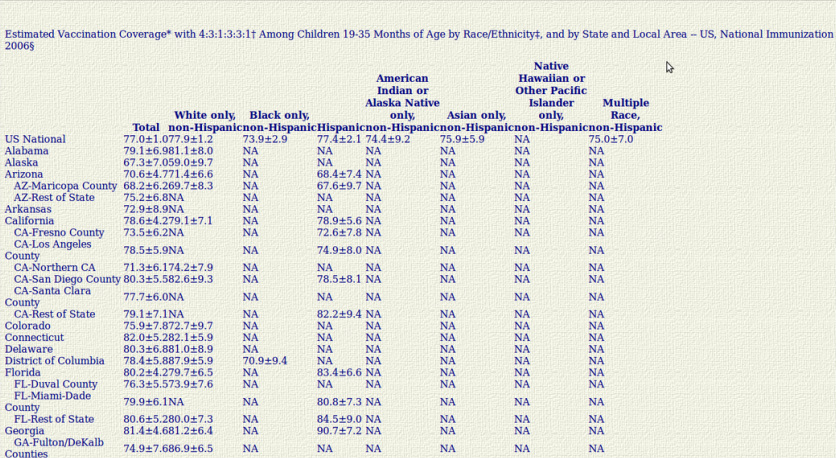

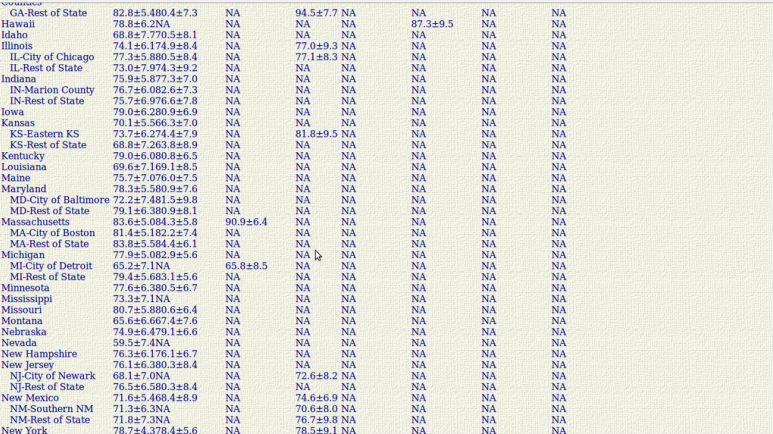

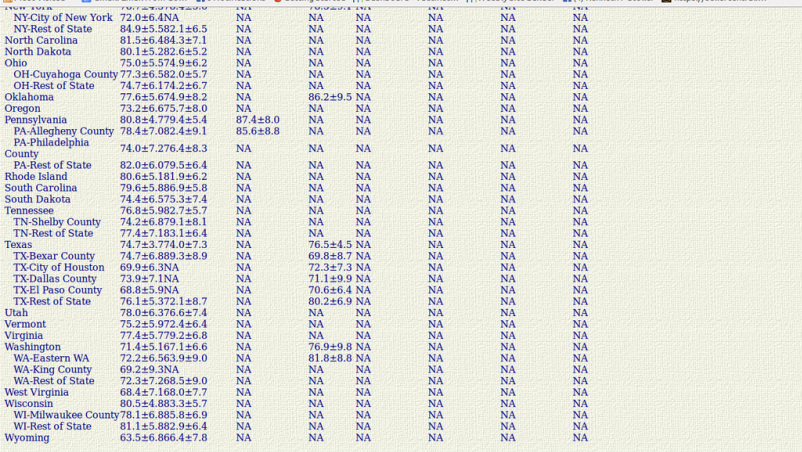

Kate Taylor did not get her children vaccinated against chickenpox because she believed they had the illness before she adopted them. Her daughter later came down with chickenpox and became so sick that Taylor took her to a hospital. "I've got a pretty good case of guilt over this, especially being a nurse," Taylor said. She has since had her son immunized. According to the National Immunization Survey released late last year, only 63 percent of Colorado children in 2002 had received five major vaccines: for diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough; polio; measles; hepatitis; and meningitis. The random telephone survey, which covered children ages 19 months to 35 months, found that Colorado fell particularly short in giving kids four or more doses of the vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough. For a time, the state did not require the fourth shot because of a national vaccine shortage.

Robert Brayden, president of the Colorado Children's Immunization Coalition, said the number of whooping cough cases in the state is three times the national average. State records show 469 cases in 2002, 389 in 2001 and 488 in 2000. Colorado pediatric hospitals also spent $13 million treating children infected with diseases that could have been prevented with vaccines in 2002, according to a study by Children's Hospital. "That's just the tip of the iceberg because these are just hospitalized children," Anderson said. "We didn't include cases where children were not severe enough to be hospitalized."

Some of Colorado's unvaccinated children are from families who cannot afford primary care doctors.

Last year, the Legislature allocated nothing toward vaccinating uninsured and poor children, and it capped enrollment in the state's Child Health Plan Plus program, which insures children from poor families. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment later redirected $400,000 for immunization funding and Gov. Bill Owens allocated $500,000 in federal money.

Colorado needs a stronger public health structure to make sure poor children get their shots, Brayden said. The state in 1997 began working on a registry to remind parents when doses are due, but it is not yet complete. About 2 percent to 3 percent of Colorado parents refuse vaccines on principle. Dawn Winkler of Gunnison said she believes mercury in vaccines led to the death of her 5-month-old daughter eight years ago. She refused any shots for her son, now 7. (Many vaccines used to contain a mercury-based preservative called thimerosal.)

"After my daughter died, it was agonizing to decide for my son," she said. "I'm not anti-vaccine, but it's a medical procedure that involves risk."

Colorado Last in Child Immunization Rate

Colorado Ranks Last in Government Survey of Child Vaccination Rates; Poverty, Shortages Cited

The Associated Press

DENVER Feb. 10 — Every few months, Erin Dlouhy sees a child under 2 at Samaritan House who has never had shots for polio, measles or whooping cough. Other children at the homeless shelter lack medical records and have to endure the painful shots again. "I would say at least 50 percent of the time, kids need to be caught up," said Dlouhy, coordinator of children's services at the shelter.

For reasons that include poverty, a lack of government funding and a national shortage of the whooping cough vaccine, Colorado wound up last in the government's most recent survey of child vaccination rates.

"We're at the bottom of the barrel," said Dr. Marsha Anderson, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Children's Hospital in Denver. "Our goal should be to be in the top 10 to be able to provide adequate coverage of our children."Health advocates say children in a state proud of its well-educated and healthy population are at risk because of funding cuts at the state and local level. They also say some parents simply do not have the money to pay for the shots or lose track of what is required.

Kate Taylor did not get her children vaccinated against chickenpox because she believed they had the illness before she adopted them. Her daughter later came down with chickenpox and became so sick that Taylor took her to a hospital. "I've got a pretty good case of guilt over this, especially being a nurse," Taylor said. She has since had her son immunized. According to the National Immunization Survey released late last year, only 63 percent of Colorado children in 2002 had received five major vaccines: for diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough; polio; measles; hepatitis; and meningitis. The random telephone survey, which covered children ages 19 months to 35 months, found that Colorado fell particularly short in giving kids four or more doses of the vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough. For a time, the state did not require the fourth shot because of a national vaccine shortage.

Robert Brayden, president of the Colorado Children's Immunization Coalition, said the number of whooping cough cases in the state is three times the national average. State records show 469 cases in 2002, 389 in 2001 and 488 in 2000. Colorado pediatric hospitals also spent $13 million treating children infected with diseases that could have been prevented with vaccines in 2002, according to a study by Children's Hospital. "That's just the tip of the iceberg because these are just hospitalized children," Anderson said. "We didn't include cases where children were not severe enough to be hospitalized."

Some of Colorado's unvaccinated children are from families who cannot afford primary care doctors.

Last year, the Legislature allocated nothing toward vaccinating uninsured and poor children, and it capped enrollment in the state's Child Health Plan Plus program, which insures children from poor families. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment later redirected $400,000 for immunization funding and Gov. Bill Owens allocated $500,000 in federal money.

Colorado needs a stronger public health structure to make sure poor children get their shots, Brayden said. The state in 1997 began working on a registry to remind parents when doses are due, but it is not yet complete. About 2 percent to 3 percent of Colorado parents refuse vaccines on principle. Dawn Winkler of Gunnison said she believes mercury in vaccines led to the death of her 5-month-old daughter eight years ago. She refused any shots for her son, now 7. (Many vaccines used to contain a mercury-based preservative called thimerosal.)

"After my daughter died, it was agonizing to decide for my son," she said. "I'm not anti-vaccine, but it's a medical procedure that involves risk."